Nick Bockwinkel: 11-23-2015 issue of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter by Dave Meltzer.

The following is the abridged version recorded for the When It Was Cool Wrestling / DragonKingKarl Classic Wrestling Podcast as appears at WrestlingObserver.com.

There were few men in modern pro wrestling who had the amount of respect among their peers as Nick Bockwinkel, who passed away on 11/14/2015 at the age of 80.

Perhaps the best example was seven months ago, in what was his last public appearance, on 4/14/2015. Nick Bockwinkel was at the Cauliflower Alley Club's Baloney Blowout. In a cruel twist of fate, Bockwinkel, the man noted for his great mind and verbal ability, fell victim to issues far too familiar to older wrestlers and contract sports athletes, with their memories and what made them tick taken away from them.

It had been kept quiet that Bockwinkel was having issues, until Ric Flair mentioned it. His friends had talked about it for years, and were heartbroken about it. I can sympathize, because my last conversation with Bockwinkel, a few years ago, was almost identical to my last conversation with Red Bastien, who faced similar issues the last several years of his life. Without going into detail, he would tell me a story, and then, less than five minutes later, tell me the same story. When someone you learned so much from is like that, it was really heartbreaking, and even more so when it was someone who throughout his life was known for his intelligence and his ability to teach.

At the Cauliflower Alley banquet, I was told that Nick Bockwinkel didn't even recognize a lot of his friends, although one person noted he was asking about his friend Patrick Patterson the first day. On the second day, at the Baloney Blowout, Brian Blair, who had replaced Bockwinkel as the figurehead President of the Club, announced that forever more, the Tuesday night event will be called the Nick Bockwinkel Baloney Blowout. As Bockwinkel was leaving, Blair asked everyone in the room, filled with his contemporaries, many of the most ardent fans, and many younger wrestlers, to give him "one last standing ovation." The description to me is that seeing everyone look at him, stand up and give him a big reaction was something he could no longer understand completely. He bowed his head and tears rolled down his face. He and wife Darlene left the room. Most in the room realized it was the last time they would ever see him as he wasn't going to be attending the banquet the next night, and the word was out this was going to be his last public appearance.

His friends said he was suffering from Alzheimer's, something his family denied and was furious had gotten out. Bockwinkel was a proud man with a great reputation and his family, and those at the Cauliflower Alley Club, were unhappy at Ric Flair, who had great reverence for Bockwinkel and who noted how much he helped him when he was a rookie, and later me (Dave Meltzer), for mentioning his issues.

Mick Karch, who in the 70s was the President of the "Worldwide Bockwinkel Brigade," considered the top fan club for any pro wrestler of that era, was there.

Karch had slowly over the years won Nick Bockwinkel's trust, after agreeing to allow him to run his fan club. He ended up giving him more time and cooperation than almost any wrestler of the era did to their fan club. Then, some 15 years later, after seeing tapes of Karch announcing for Tony Condello in Winnipeg, suggested to Verne Gagne to hire Karch, who then became an AWA announcer and interviewer.

He also recognized this was probably the last time he'd ever see Bockwinkel.

"It was so surreal to me," wrote Karch in an article for Slam!

Wrestling. "So much history between us, my mentor, my friend, was riding off into the sunset.

Bockwinkel was sitting down with his wife, Darlene, and Karch came up to him and said, "I love ya, Bockwinkel. You know that, don't you?" Bockwinkel said, "You do, huh?"

"I felt a lump in my throat and said, `Damn right.' With that, Nick started to cry, which promoted me to do the same. I looked at him and said, `Nick, I wouldn't be here, I wouldn't have any of this, if it wasn't for you.' We shook hands and I went on my way, leaving him to bask in the glow of the adoration he was receiving from everyone."

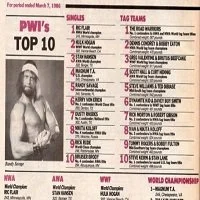

Most will remember Nick Bockwinkel with the huge gaudy belt, the "giant license plate," as he would sometimes jokingly refer to it, in his words, "emblematic of being the best wrestler in the world." He was a four-time AWA champion, the dominant champion from 1975 through 1987, and the most widely traveled champion in the history of what was considered during that period as one of the big three titles in North America.

But he had a sense of humor about it. In the business, through at least the end of 1983, most considered the NWA championship as the leading belt in the industry. Bruno Sammartino was the biggest drawing card in wrestling during his heyday and the WWWF title he and Bob Backlund dominated covered the Northeast, including the most populous cities and Madison Square Garden, the NWA belt was recognized in far more places. Bockwinkel's AWA title belt was the king in the Midwest, where he, like Verne Gagne, The Crusher, Baron Von Raschke and others, were symbols of a golden era, household cultural names, for people who grew up in cities from Chicago to Denver, Winnipeg to Omaha, and most points in between.

Nick Bockwinkel, as champion, wrestled at times in a number of NWA and unaffiliated territories as champion, including strong wrestling markets like Houston, San Antonio, Tennessee and in Alberta, where his title supplanted the formerly recognized NWA belt as the key title the local stars would chase. Many would consider the Bockwinkel & Bobby Heenan duo as champion and manager to be the best all-around package of its type in at the time, and arguably ever, as far as a top star/manager combination. The closest modern comparison would be the heel C.M. Punk's long title reign with Paul Heyman as manager. Punk, like Bockwinkel, was a great talker on his own, and one could argue didn't need a manager. But the manager made the championship act that much more effective. The Punk/Heyman act was together only a short time, while Bockwinkel and Heenan were together, on-and-off, for a decade.

During that era, in Japan, Ribera steakhouse, a small hole-in-the-wall place in Tokyo was a hangout of wrestlers, made famous by the Ribera jackets that the biggest stars would wear in public. The place featured autographed photos of the biggest stars as they ate there. Harley Race, Bockwinkel's contemporary as NWA champion, signed his photo, "Harley Race, six-time REAL world champion," with the idea that the NWA always pushed that there were other champions, but the NWA belt was the real one, claiming its history dated back to the Gotch-Hackenschmidt days.

The National Wrestling Alliance was actually the name of a regional world title in the 40s, which became the major worldwide alliance of promoters from a meeting in 1948, the top organization as it grew in popularity by 1949 and created the closest thing to a worldwide recognized world champion within a few years due to the booking and political savvy of President Sam Muchnick and the respect of perennial champion Lou Thesz. Muchnick had commissioned a history, not completely accurate, but not far from accurate, tracing an NWA world title lineage to those famous matches.

Bockwinkel, in autographing a photo and seeing what Race wrote, signed his, "Nick Bockwinkel, three-time semi-real world heavyweight champion."

"He was one of the brightest guys, in or out of the business, that I ever met," said Ring of Honor Vice President of Operations Gary Juster, who grew up in the Twin Cities as a fan watching Bockwinkel. It was Bockwinkel who was responsible for getting him into what was a very closed business in that era. "He was incredibly classy, up on world events, super quick witted. He mentored me and introduced me to Verne Gagne, and really is responsible for me getting my start in the business."

Nicholas Warren Francis Bockwinkel was born December 6, 1934, the son of Warren Bockwinkel, a St. Louis native from the days of the Businessman's Gym. The gym was more akin to a modern MMA gym than a pro wrestling training school of today, in the sense that everyone trained actual wrestling under former Olympian George Tragos. Once they were deemed good enough at actual wrestling to turn pro, then they started being taught working.

Warren Bockwinkel was five years older than the gym's star wrestler, Lou Thesz. Warren Bockwinkel broke in just before Thesz. His father's flirtation with wrestling started when he lost a fight to a wrestler from that gym, and wanted to learn the techniques used again him.

Thesz loved to tell the story about how he, early on, was holding a baby Nick Bockwinkel, who peed all over him, particularly later when Bockwinkel was a recognized world champion, and later, when Thesz was President of the Cauliflower Alley Club and Bockwinkel was Vice President.

Being the son of a pro wrestler meant traveling all over the country. Bockwinkel went to high school in San Francisco, where he was a star football player and a good wrestler. He went to high school with the daughters of the Sharpe Brothers, the dominant tag team of the era, and was a contemporary football rival of John Madden.

One day, when he was brought to San Francisco in 1997 when a Japanese television station was producing a television special on Stevens that we both were part of, we went around to his different hangouts, as he talked about growing up and watching The Sharpe Brothers, Killer Kowalski and Leo Nomellini.

His father had trained him in wrestling from the age of six.

But because his father traveled, he actually attended six different high schools around the country. He got a football scholarship to the University of Oklahoma, and was going to wrestle there as well. But he blew out his knee in his freshman year, came back, and the knee went out again.

"At a college like that, No. 1 in the nation (this was during the Bud Wilkinson era where Oklahoma won what is still the all-time collegiate record of 47 straight games), they don't keep you if you're a freshman and have had two knee operations."

He came to Southern California, and attended UCLA while also wrestling, getting a push as a new young 19-year-old star as something of a 50s teenage heartthrob type babyface. The idea was to wrestle to pay for college. He got a degree from UCLA in marketing, but ended up never using it.

He sometimes headlined in a tag team with his father, who was finishing up his career. While Bockwinkel is generally thought of as one of the great arrogant wrestling heels of all-time, he was mostly a babyface from his debut in 1954, until 1970.

He was trained for pro wrestling by his father, Thesz and Wilbur Snyder. He'd only been wrestling a few months when he won the International Beat the Champ TV title on two occasions. A few years later, using the name Dick Warren, while also doing military duty, he and Ramon Torres, of the famous Torres brothers, held the West Coast version of the world tag team title twice.

He was a star everywhere he worked for virtually the entirety of his full-time career, which ended with his 1987 retirement, at the age of 52. He could see the AWA was on its last legs, and he got an offer to come to WWF. They wanted him as a road agent and not a wrestler, even though he was still better than the vast majority of the wrestlers on the WWF roster at the time. For a promotion building around youth and steroid bodies, Bockwinkel would have been a fish out of water, and wasn't going to get a push even if they did want him to wrestle.

But times had changed. In the pre-1984 era, Bockwinkel, the veteran great worker and one of the three major champions of the business, was as highly respected as anyone. His goal was to always have a good match. He had a high opinion of his talents, deservedly so, even though he would always talk of his long-time partner, Ray Stevens, with reverence. He often would say that if Stevens was hung over from an all-night binge, and he was at his best, on those days, he was close to as good as Stevens.

His talent was creating dramatic matches with character babyfaces, most notably Crusher, or older wrestlers in the 80s like Mad Dog Vachon, Baron Von Raschke, and even Billy Robinson, as well as being the favorite opponent of Verne Gagne, the territory's owner.

When The Crusher passed away, he noted, with no attempt at false modesty, that when people would talk with him about the great sellout matches at the Amphitheater in Chicago with he and Stevens against Bruiser & Crusher, he said, "I'll take all the credit for those matches with Ray Stevens, because we deserved it."

He worked 17 straight years as a main event heel in the same territory, and was effective in that role until the promotion fell apart, never getting stale. Jerry Lawler, who worked with all the great champions of the era, had his best title matches with Bockwinkel and always called him the best world champion he ever faced. Unlike most top performers, there was no Nick Bockwinkel style match or patterned sequences of moves. He used a piledriver as a finish early, but in his world title run, he often used the figure four.

Philosophically, he was similar to Bret Hart, in the sense he was about making a match exciting, heavily relying on psychology and storytelling, while not wanting to get hurt in doing so. But he was far less patterned. That philosophy led to his longevity at the top, as he avoided the crippling injuries and was still working at the top level into his 50s. In particular, he wasn't fond of working with Wahoo McDaniel, one of the top stars of the era, because he didn't enjoy taking the hard chops. The idea was to make everything believable, lay stuff in, but without risking unnecessary injury to himself or his opponent.

"I knew how to wrestle a little bit, but I was not a Danny Hodge in any capacity," he said in the book "The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels," that named him one of the greatest heels of all-time. "I worked hard. I worked enthusiastically. I didn't want anyone to see any holes in my work. By that, I meant the guy at ringside, the 10th row of ringside, the 15th row of ringside. So I laid them in. Now, I didn't lay them in with the knuckles as much as the whole forearm. If you can't take the pounding, then God almighty, it's not a sewing circle."

But he was the conductor and felt strongly about what that role meant. As the world champion heel, he controlled the workings of his matches, and he grew frustrated with guys who wouldn't listen to his veteran advice, or guys who worked a dominating style and didn't show respect for his standing and didn't give him offense befitting his standing, pointing out names like Bruiser Brody, Stan Hansen and the Road Warriors.

When the younger bodybuilders took over from the old school wrestlers in the mid-80s, in his interviews, he would note how he and Stevens never wore scary costumes nor painted their faces, but had been main eventers for 30 years, "So think how good we must be." He would joke, "What do you call a bodybuilder with mirrors on four sides?" The answer, was, "A prisoner."

I can recall being at a show at the Cow Palace in San Francisco in the mid-80s San Francisco, where Bockwinkel was the challenger in an AWA title match against Rick Martel. They were going about 35 minutes so started slow. Bockwinkel held Martel in a long headlock and fans were chanting "Boring." Most wrestlers would have taken that as a cue to get up and do a high spot. Bockwinkel took the opposite approach. He told me that the conductor at the symphony isn't told by the audience what to do. He held Martel in a headlock even longer, and yelled at those who were chanting, saying, "Rick, you're boring your fans."

I can also recall 16 years later, sitting with Bockwinkel at the original King of Indies. Unlike most wrestlers of his era who weren't as open-minded to changing styles, Bockwinkel enjoyed the tournament that included some of the best young wrestlers of the time, such as Bryan Danielson, Samoa Joe, A.J. Styles, Christopher Daniels, Brian Kendrick, Doug Williams and Low Ki. As Danielson was wrestling Kendrick, he was beaming, talking about how when he was champion, he would loved to have shared the ring with someone so talented. He said guys of his era didn't like giving the modern wrestlers credit, but that Danielson was as talented as anyone from his era, which is notable because in his era, a guy the size of Danielson would have never gotten a push when you had to be heavyweight size (or, like Greg Gagne, the son of a promoter) to headline in a major money territory.

When the match was over, he, Red Bastien and much of the audience stood up and gave both men a standing ovation. And then he left. He came back several minutes later and I asked where he went, and he said he went to find Danielson to tell him that in his heyday, he'd have been proud to work on the same card as him.

The plan for the King of Indies, promoted by Roland Alexander in 2001, was for Donovan Morgan, Alexander's head trainer, to beat Danielson in the semifinals and Low Ki in the finals. It made the most business sense, putting your own guy over.

The Danielson vs. Kendrick match took place on the first night. After the show, Bockwinkel went to Alexander, and said, "If you don't put that guy over, you're crazy," pointing to Danielson. Alexander had so much respect for Bockwinkel's opinion, that he not only changed the finish, but in order to make it make sense for his business, also offered Danielson the head coaching position at his school.

Bockwinkel's first match with Gagne's AWA may have been in 1962 (he had matches in Jim Barnett's AWA, the American Wrestling Alliance as opposed to Gagne's American Wrestling Association years earlier), coming in as the tag team partner of local star Tiny Mills in a tournament for the vacant AWA tag titles (Otto Von Krupp, who was later better known as Professor Boris Malenko, who held the titles with partner Bob Geigel, was injured). As the outsider, his team lost in the first round.

He was a star in a number of territories as the dark haired crewcut babyface, looking somewhat like football star Johnny Unitas. It wasn't until late in his career when he grew his hair out and colored it frosty blond as a heel.

In 1964, while working in Oregon, he and Nick Kozak formed a tag team, feuding with The Destroyer (Dick Beyer) & Art Michalik, who were part of a three-man unit of ex-football stars with Don Manoukian. Michalik was best known as the man responsible for the invention of the face mask in the NFL. While playing with the San Francisco 49ers, he smashed his elbow into the face of football legend Otto Graham of the Cleveland Browns causing a concussion and splitting his lip and cheek open. Paul Brown, the coach of the Browns, then sent Graham back into play with a face bar added to his helmet.

But the most famous part of Bockwinkel's career started in late 1970, when he returned to the AWA, and got over so strong as a heel, that it remained his home base until the end of his career.

His first heel run started shortly before his AWA debut. He was wrestling in Georgia as a babyface, holding the Georgia heavyweight title. When world champion Dory Funk Jr., would come to town, Bockwinkel got regular shots at him, always coming up short. The frustration at being unable to beat Funk Jr. led to a slow heel turn.

Bockwinkel traced the turn to one interview.

"I said, `Webster's Unabridged Dictionary, page 1,348, the far right column, the 36th word down is `Funk.' F-U-N-K. Definition–to retreat in terror, to be afraid, to be not confident.' I slammed the other half of the book closed. I said, 'Thank you,' and I walked off. The TV station said they got more response, the office got more response, just out of that little tidbit."

Funk Jr., who was NWA champion from 1969 to 1973, said that he rated Bockwinkel at the top of the list of his challengers, right along with Jack Brisco, Harley Race, Johnny Valentine and McDaniel.

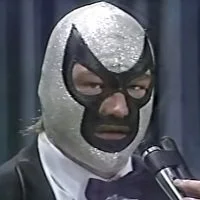

When he arrived in the AWA, he had somewhat long, thick, blond hair. Bockwinkel had a natural arrogance and billed himself as being a rich sports star who lived in Beverly Hills, CA, with the idea he ran in the same social circles as the A-listers of the era. He would refer to the wrestling fans as "cretinous humanoids," (Bobby Heenan calling fans humanoids came from copying Bockwinkel) and "8 to 5 lifers."

He had done some acting, usually working as a bad guy heavy when they wanted a big guy with a good physique and that was also good looking. He had a small role in an episode of "The Monkees" TV show, and, while living in Hawaii, was on the original "Hawaii Five-O," television show a few times. He wasn't a workout fanatic or a steroid guy, but was blessed with good genetics and structure, able to carry about 240 pounds on a 6-foot-1 frame and have a very fit athletic looking body. Between maintaining a tan and his genetics, the body allowed him to look years younger than he was, particularly in a period when steroid use wasn't so prevalent so people's views of an athletic physique hadn't been as warped.

His few acting credits in wrestling in those days was parlayed into the idea he was a Hollywood TV star, which played well to fans in the Midwest where those type of people were outsiders in their more rugged cultural of living in a far more brutal climate. During his entire AWA run, they would pretend he lived in Beverly Hills, not Minneapolis, and commuted to the area, while bragging about how much better things were, from the weather to the women, where he lived.

"The Lean Mean Machine, Tricky Nicky Bockwinkel," quickly became the leading singles rival of Verne Gagne, the Minnesota sports hero and Midwest wrestling legendary world champion. The contrast also worked with the California pretty boy going against the street fighting legend, the cigar chomping and beer-drinking Crusher from Milwaukee.

When Gagne brought in Ray Stevens several months later, billed from San Francisco, where Stevens was the wrestling legend, he paired the two of them up. They quickly defeated Bastien & Crusher for the AWA world tag team championship on January 20, 1972, in Denver. With a few brief interruptions, they held those titles until August 16, 1975, losing to Crusher & Dick the Bruiser, in Chicago.

Because Gagne only wrestled sparingly, maybe 15 to 20 title defenses a year, the house show business was largely built around the tag team championship. The two were considered the premier tag team in the business during that era, and also worked outside the AWA in places like Florida and Texas. The Bockwinkel & Stevens era as champions, working against various combinations of babyfaces like Crusher, Bastien, Billy Robinson, Don Muraco, McDaniel, Dr. X (Dick Beyer), Gagne, Bruiser and Ken Patera, was the AWA's best drawing era until the Hulk Hogan era in the early 80s. At first the team went solo, but later added Heenan to the package as manager.

Teaming with Stevens was one of Bockwinkel's career highlights. He noted that he worked in San Francisco in the early 60s when Stevens set the area on fire and was regarded as the Ric Flair or Shawn Michaels of his era. He would talk about how he and Wilbur Snyder were the world tag team champions working underneath the Stevens vs. Pepper Gomez U.S. title feud, the biggest in the history of the area. Stevens to him was the gold standard. Whenever he would praise someone in the ring as being one of the best, the term was, "He was almost as talented as Ray Stevens." Gomez was another personal favorite. He noted to me when Gomez passed away that, "I named my dog `Pepper,' and that is the highest honor in my household."

The two were among the greatest and most successful tag teams of all-time. Both specialized in making their opponents look good, but had the ability to always stay over. It helped that they usually cheated to win, with the favorite finish being Stevens doing the Bombs Away, a kneedrop off the top rope, a move illegal in the AWA, behind the referee's back.

The two were a contrast with the erudite' Bockwinkel, who exuded class, dressed well and used big words in his promos like a college professor, and Stevens, gruff, who was like the kid in high school who was constantly in detention for looking up girls skirts.

Some of their best work came on promos when they would do shots in Honolulu, where Bockwinkel, who had previously been a top babyface when he was a regular on the islands, would speak eloquently, and then Stevens would look at Lord James Blears, a British transplant who booked the promotion and hosted the television show, and close the interview saying, "There's only two good things that ever came out of England , and Elizabeth Taylor's got both of them."

Nick Bockwinkel's interviews came because he had a little notebook, and whenever he'd read a multi-syllable word he didn't know, he would go to the dictionary, and put the meaning in his notebook, and figure a way to work it into his promos.

"I used the four, five or six syllable words as best I could," said Bockwinkel.

He'd study 70 or 80 words in his notebook and when he would do his interviews, which were usually off the top of his head, the words would come naturally to him.

Flair was breaking into wrestling in late 1972, and while he palled around with Superstar Billy Graham, and was enamored with Stevens and Dusty Rhodes, he had great respect for Bockwinkel.

"Nick was one of the greatest guys I ever met in my life," said Flair. "He wasn't Ray Stevens or Dusty Rhodes, but he was a great promo. He was the modern day Buddy Rogers, dressed like a star, great technician,, really nice guy. I wasn't mesmerized by him like I was with Ray and Dusty, but every day he would call me aside to give me advice. He meant a lot to me. He became a great friend. He was a great wrestler, a great champion and a great representative of our business. 8-to-5 humanoid lifers, what a great promo back then."

Even though Ric Flair started his career in the AWA, he was a prelim wrestler and Bockwinkel was a headliner. The two may have only wrestled once in singles, on January 16, 1986, in Winnipeg, going to a long double count out in a very good, but not a blow away match. It's funny because people who grew up in the city, and even those in the match like Flair, often recalled it as a title vs. title match. But the match was held when Bockwinkel wasn't AWA champion and only Flair's title was at stake, which was highly unusual since the NWA title was never defended in Winnipeg otherwise. Many in the city also remembered it as a 60 minute draw, which it also wasn't. Because of who was involved, many also remember it as the best match of the era at the Winnipeg Arena, whether it was or wasn't.

Chris Jericho grew up in Winnipeg during that period, when a huge percentage of people in the city would watch the AWA television show and then Hockey Night in Canada. While the story goes around that Jericho was in the front row of the Flair vs. Bockwinkel match, he said that wasn't the case. The well dressed and well-spoken heel that Chris Jericho reinvented himself as in 2007 for his first comeback after a multi-year sabbatical, and led to the best run of his career, was from a combination of characters, but much of it, particularly the way he dressed, the hair and the promo style, was taken from the heel champion character that Bockwinkel played.

"So when I had the idea to turn heel in 2007, because I felt I was very stagnant as a babyface, I based it around two things," said Jericho. "One was a character in the movie, `No Country for Old Men,' a straight forward no-nonsense serial killer who talked very slowly and very deliberately, and the other was Nick Bockwinkel.

"The WWE had just put out the AWA DVD and I watched it and remembered how great Nick Bockwinkel was. I started wearing the suits that nobody was wearing at the time, and also took his delivery on promos, not yelling, not screaming, very matter-of-fact, very intelligent, using those big words, talking over people's heads. I remember watching as a kid, I didn't like him, because he was a heel, but one of the reasons was he talked over everyone's head and he was holier than thou. When I talked to him in Las Vegas, he said, `Big words equals heat. Use big words that people don't understand and it will piss people off because they'll know you're smarter than them and nobody wants to be reminded people are smarter than them. Nobody likes to feel stupid.' So that's where I got the basis of the character. A lot of it was Bockwinkel for his use of those big, big words."

The title loss was to move the focus of the promotion from the tag team title to the AWA title, with Bockwinkel as champion. He defeated Verne Gagne on November 8, 1975, in St. Paul. The win, to those in the Midwest, was a total shock, as Gagne had held the title since beating Mad Dog Vachon on February 26, 1967. There was a two week title reign in 1968 by Dr. X, Dick Beyer, in the Twin Cities, but the rest of the territory never knew about it, so to most fans, Gagne had been champion for eight years and eight months straight, and had beaten Bockwinkel numerous times in every city over the previous five years.

That was part of the psychology, because Bockwinkel was the perfect opponent for Gagne to chase, and the promotion was always about placating Gagne's ego. Since Gagne didn't work full-time, the storyline was that Bockwinkel was refusing to give him title matches. The fans all knew that when Gagne was champion, he beat Bockwinkel numerous times, and that Bockwinkel knew it as well. So when Gagne would get a rare title shot, people thought he'd get it back since they were so used to Gagne always being the world champion. But Bockwinkel, for years, would always escape with some sort of technicality. And he was able to make the aging Gagne look like he was the same Gagne that everyone remembered even though by this time Gagne and Crusher were both in their 50s. In addition, he had the ability to make Greg Gagne, Verne's son, look like a potential world champion when they worked together.

During this period, Bockwinkel once even retained his title doing what may have been Andre the Giant's only 60 minute draw, which he admitted was not one of his better matches, but he didn't think anyone else ever did that with Andre.

As far as the portrayal of a world champion, Bockwinkel, was one of the classic champions of modern times. While champion, he was approached by Jack Adkisson (Fritz Von Erich) and asked if he was interested in becoming the NWA champion.

The NWA title in that era made you viewed by many as the biggest star in pro wrestling, and with the exception of Andre the Giant and Bruno Sammartino, would have made him the highest paid wrestler in North America. Virtually everyone in the business wanted the title. It have you a worldwide legacy, and even after losing, just having held it once in your career made you a star in most parts of North America as well as Japan .

Bockwinkel told me he considered it, but then thought that he was making about $150,000 a year, which was very good money in the 70s, and working about 180 dates, while based in one territory. He also had a relaxed summer schedule since the AWA cut down on dates during the warm weather with the idea those in the Midwest would take vacations, plus Crusher would routinely invent a problem with Gagne just before the summer would start, have a fight, and quit, taking the entire season off, before calling to make up when the weather would start to get cold. Bockwinkel said he didn't know, but he figured that Race, the NWA champion, was making about $350,000 a year working more than 300 dates (and his estimate of Race's pay may have been high), and felt it just wasn't worth it.

Nick Bockwinkel was very strong in thinking business. He was part of the AWA's booking meetings from the mid-70s until leaving the organization. In the early 80s, figuring his active career was coming to a close, he bought a percentage of the Houston office from Paul Boesch. Boesch had become disenchanted with the NWA after Race had no-showed two dates for him. To illustrate just how much Boesch hated no-shows, the two matches Race missed as champion were four years apart, one in 1977 and the other in 1981. The second one caused Boesch to recognize Bockwinkel as his world champion. Bockwinkel faced a steady stream of the top babyfaces of the era that Boesch would bring into town, different foes than he'd meet in the AWA, like Bruiser Brody, Dusty Rhodes, Junkyard Dog, Tommy Rich, Tony Atlas, Mil Mascaras, Chavo Guerrero and others.

As a part-owner, Bockwinkel made sure to appear regularly in Houston. Boesch was one of the best paying promoters, and as part owner, if he could help draw a big house, it meant a double payoff. His idea was that when his career was over, he'd move to Houston and eventually, when Boesch retired, take over the promotion.

But wrestling changed and the regional office concept was gone by the time Bockwinkel retired. Instead, after his time as a road agent in WWF was over, he instead became an insurance salesman and financial planner. He eventually moved from Minnesota to Las Vegas in 1999, where he spent a lot of time on the golf course. He also had a short run as the figurehead commissioner of WCW in 1994. The idea sounded good on paper, as Bockwinkel had the credibility of being a legendary performer, and talking was his strong point, but it wasn't a good mix, and didn't last very long. He also helped promote some WCW shows when they came to the Twin Cities.

But as much as he did think business, he also thought lifestyle. He had told me that his favorite period of his career was not when he was one of the biggest names in the business in the 70s and 80s, but when he was a major star in Hawaii during the 60s.

He noted that people all over the world would work hard all year and save up money so they could take their families to Hawaii for a week or two. He, on the other hand, had an apartment across the street from Waikiki Beach, was working three shows a week, which meant he could go to the gym every morning, hang out at the beach every day while his kids were in school, and be home with his family several nights. And when he did work, they were either short drives, or short flights to the other islands. The money wasn't big, but it was enough to live on. He noted that his kids (two girls, Johnna, born 1958, and Nikki, born 1961) got to live and spend months at a time, year-after-year, on separate occasions living in Hawaii when they were young, and they had great childhood memories of the period. He called the period one of the highlights of his life, saying it was like a long vacation, and when it was over, it cost him no money.

Hawaii was almost his regular territory for most of the 60s, living there from April through August of 1962, from April through September of 1963, from September 1964 through May 1965, from January through October in 1966, from March through December of 1967, from October 1968 to May 1969 and for the month of November of 1970, before his start in the AWA.

Bockwinkel's first title reign ended on July 18, 1980, when he lost to a 54-year-old Gagne. It was a pure vanity move. Gagne was the perennial top contender during Bockwinkel's title run. In a territory built around the very limited Crusher as its top draw, having a top heel with the ability to make limited performers look good was a must, and that was the key to Bockwinkel's long run on top.

Gagne planned on retiring with a big show the next year, and wanted one last title run. Gagne's original retirement match was May 9, 1981, before 15,780 fans at the St. Paul Civic Center, where he pinned Bockwinkel. But then in a shock, on television, AWA figurehead president Stanley Blackburn announced that with Gagne vacating the title by retiring, that it would take months to do a tournament involving the top contenders around the world, so he was instead awarding the title to the No. 1 contender, Bockwinkel. It made no sense of course. The irony is that the decision was made by Gagne, the promoter. But Gagne, the television performer, who would try and keep sports credibility in his crazy world, was furious. He noted that the Olympics involves wrestlers from all over the world and they can get a tournament done in a few days, and, leaving the door open for a comeback, strongly hinted that if he knew the title would be given to Bockwinkel, he may not have retired.

Ironically, it was this next run that was the most financially successful. Largely due to the emergence of Hogan as pro wrestling's biggest drawing card, the AWA caught fire. While Hogan was the big draw, the main events usually featured Bockwinkel, with Heenan by his side, defending the title, often against older babyfaces and making them look young again.

In a move that came out of left field, even though business was on fire, Gagne basically sold the AWA title for a short run to Otto Wanz, the top star in Germany and Australia. Wanz, who was an unknown in the U.S., came in with a push and shocked everyone pinning Bockwinkel on August 29, 1982, at the St. Paul Civic Center.

Few know the story, but this match started a chasm between Bockwinkel and Heenan behind-the-scenes. Bockwinkel clued nobody, not even Heenan, in that he was dropping the title. Heenan felt, and deservedly so, after such a long affiliation with Bockwinkel and Gagne, that, being at ringside, he deserved to have been clued in on that finish. While not enemies, for years Heenan would bring that up when the subject of Bockwinkel came up. For his part, Bockwinkel would never say a bad word about Heenan. He always praised him, calling him "Sir Robert," in reverence because he was so good at what he did he should be knighted. He also praised Heenan as an underrated wrestler, noting that if for some reason he or Stevens had to miss a show when they were carrying the territory as a tag team, that they could put Heenan in as a replacement and not miss a beat.

Bockwinkel regained the title on October 9, 1982, in Chicago. Wanz was then able to return home, and claim he went to the U.S. and won one of their major world titles, to give him credibility back home as not just a local star, but a worldwide star.

With Hogan as the top draw, there was the argument that he should have gotten the title. The reality is business was great the way it was. Bockwinkel would wrestle Hogan on occasion, always ending in a DQ finish because Hogan wasn't going to do a 60 minute match, nor did Gagne ever suggest Hogan lose. It was difficult because some kind of a match with a finality stipulation, like a no DQ match, Texas death match or cage match, with Hogan, would have drawn the biggest gates possible, but they were impossible to book.

It turned out to be for the best it didn't happen, although historically, things would have long-term ended up no differently. Had Hogan won the title and beaten Bockwinkel, he would have left a few months later for the WWF without doing a job and as the real world champion to every fan in the Midwest. Bockwinkel, even at 49, was the best person Gagne would have had as champion and he at least could claim that Hogan had many shots at him and never won. While going back to him as a default champion when Gagne retired worked out fine, that was because Gagne wasn't the top star working for the opposition.

Still, Gagne didn't know what was coming at the time. Gagne had reservations about giving the title to Hogan, in the sense he didn't need it. Hogan was booked similarly to Crusher, and Gagne hadn't put the title on Crusher since 1965, and never long-term. The difference is, Gagne booked Crusher to lose very rarely, usually to build up a big gate for a return. He never booked Hogan to lose because with Hogan, no revenge for a loss had been needed before he left. Plus, Hogan's main money was not in the AWA, but in Japan, and New Japan would have not wanted Hogan to lose to anyone if he wasn't going to lose to Antonio Inoki again (Inoki beat Hogan early on, but once Hogan became a big star in the AWA, Inoki never pinned him or beat him via submission).

There was also a political issue. Gagne had a deal with Giant Baba to where the AWA champion would work for All Japan Pro Wrestling. Hogan had a deal with rival New Japan, starting when Vince McMahon Sr. booked him when Hogan was still working for WWF during his first run with the company as a heel managed by Fred Blassie. Gagne tried to get Hogan to switch sides and give him the title, but New Japan was Hogan's big money at the time, as he was a far bigger star in Japan than in the U.S. Plus, if the belt was on Hogan, he'd be gone for long periods of time in Japan. With Bockwinkel, they could have title matches on every show, although the AWA flourished in the 70s with rare singles world title matches.

The biggest show ever in the Twin Cities, at least until WrestleMania goes there, "Super Sunday," took place on April 24, 1983, with a double main event of Bockwinkel vs. Hogan for the title, and a grudge match with Verne Gagne coming out of retirement to team with Mad Dog Vachon against Sheik Ayatollah Jerry Blackwell & Sheik Adnan Al-Kaissie. They sold out the 18,000-seat Civic Center well in advance, and opened up the St. Paul Auditorium for closed circuit, drawing another 5,200. They did the Dusty finish, years before it got that nickname. There was a referee bump and while the ref was down, Hogan flipped Bockwinkel over the top rope. Hogan then pinned Bockwinkel with a legdrop after the ref recovered, and Hogan was awarded the title. However, Blackburn reversed the decision, noting that at the point Hogan threw Bockwinkel over the top, it should have been a disqualification.

Hogan had so much momentum that fans were furious. But if anything, making Hogan the uncrowned champion made him stronger. At some point, a decision would have had to have been made, and the Japan issue made it touchy. But Hogan left well before that point.

Gagne sold another short-term title change, this time to All Japan. Baba had bought a few one-week title runs from the NWA for himself. Knowing his days as the top star in the promotion were over, Baba purchased a run for Jumbo Tsuruta, his heir apparent as the top star. Tsuruta beat Bockwinkel on February 22, 1984, in Tokyo, in a match at Budokan Hall in Tokyo, with Terry Funk as referee, in a match where Tsuruta also put up his International title.

Tsuruta, unlike Baba and Antonio Inoki, when they won the U.S. world titles, actually toured the U.S. as champion, with the idea it gave his standing as a world champion more credibility in Japan. He worked all the major AWA cities, before losing to Rick Martel on April 13, 1984. It was sad later in life when honoring Martel, a frequent opponent, at Cauliflower Alley and in other places when the subject of Martel would come up, Bockwinkel would talk of how proud he was to drop the title to Martel.

Martel and Bockwinkel headlined in numerous title matches during this period. Once, in Memphis, they actually had Bockwinkel come in as AWA champion, even though Martel was the champion, to defend against Jerry Lawler, since a few years earlier the Lawler vs. Bockwinkel program was so strong, and they left Martel wouldn't be as effective as Bockwinkel as an opponent for Lawler.

In fact, Lawler sort of won the title himself. On December 27, 1982, Lawler beat Bockwinkel, but Bockwinkel got his foot on the ropes and the referee counted to three. Lawler was announced as the new champion, and they had the celebration. This was only acknowledged in Memphis and the territory, and I believe they later ruled that the title was held up pending the rematch two weeks later.

During the interim week, on January 3, Lawler destroyed Jimmy Hart so badly in a match that Hart was said to be injured so badly, he was going to be hospitalized all week. In a booking masterpiece, Hart still vowed to be in Bockwinkel's corner the next Monday for revenge to make sure Lawler didn't get the title.

On that night, Hart appeared to be in Bockwinkel's corner (even though this was before Bobby Heenan left for the WWF, Jerry Jarrett wasn't bringing Heenan in with Bockwinkel) wrapped up with bandages from head-to-toe. Just as Lawler appeared to be on the verge of winning, the real Jimmy Hart ran to the ring and distracted him. Lawler and the crowd were stunned, Bockwinkel snuck up and got the pin, and the man wrapped up in the bandages revealed himself to be Andy Kaufman.

Bockwinkel finally turned babyface in the AWA, and on June 29, 1986, was scheduled to win the title in Denver from Stan Hansen. Hansen, a regular with All Japan, was caught in a political problem. He had a title defense scheduled for Japan against Tsuruta several weeks later. Baba once again played a part in getting Hansen, his top foreign star, the AWA belt. Tensions between Gagne and Hansen were high, and there was fear that Hansen, who almost never did jobs in those days, wouldn't lose the title. He wasn't told ahead of time about dropping it in Denver, but did have a sense something was going to happen. He showed up, found out he was supposed to lose that night, and walked out, taking the belt with him.

This was the end of the oversized license plate belt that Gagne and Bockwinkel had made famous, as Hansen ran over it with his truck before mailing it back in tatters, after he'd gone to Japan and defended it against Tsuruta.

So once again, Bockwinkel was champion without having beaten the champion. He tried his best, claiming that Hansen knew he was cornered and turned tail and ran out of the building in Denver. Since Bockwinkel was a babyface, fans were happy he was champion, but by this time the AWA was struggling badly. It was during this reign that Bockwinkel had his 60 minute draw on ESPN against Hennig, which was taped in Las Vegas in November, but aired on New Year's Eve.

His final title run ended unexpectedly. At the Cow Palace in San Francisco, at Superclash, Curt Hennig pinned Bockwinkel on May 2, 1987, due to outside interference from Larry Zbyszko, who handed Hennig Brass Knux and he knocked out Bockwinkel for the pin. It was a changing of the guard in many ways. Stevens was in Bockwinkel's corner, and told the referee what happened. Even though Stevens was the all-time legend of Cow Palace wrestling and Bockwinkel was the babyface, the fans had completely changed by this point. They wanted to see a title change and booed Stevens for telling the ref about the interference and foreign object. The idea was to return the title to Bockwinkel. However, Hennig got an offer from WWF and was ready to go. When he told Gagne, Gagne wanted him to stay so badly he offered him the title, and Hennig accepted, which delayed his going to WWF. So the man who had been handed the belt over-and-over, lost it for the final time in a situation he never knew about and wasn't even planned when it happened to be a switch. But it was all for the better.

The AWA was dying and Bockwinkel got his WWF offer three months later. While Gagne got a huge retirement in 1981, and the big comebacks, Bockwinkel's career as a full-timer ended quietly. As best we can tell, the last match of the Bockwinkel & Stevens team came on June 9, 1987, in Green Bay, beating Zbyszko & Brian Knobs in a co-main event before 175 fans. Bockwinkel's farewell was on August 2, 1987, in Oshkosh, WI, putting over Hennig in an AWA title match, making him a headliner and championship match participant to the very end.

There was some humor in his WWF run, since the road agents were the guys who broke up pull-aparts and beatdowns. Heenan was an announcer by that point, and one of the rules of thumb is you couldn't mention the name of the former wrestlers breaking up the skirmishes, and there was even once an incident where Heenan had to pretend not to know who Bockwinkel was while broadcasting.

Bockwinkel ended up having a brief tryout as an announcer, and did four more matches after that point, a legends Battle Royal in 1987 (the only WWF match of his entire career, although he did wrestle Bob Backlund in a title vs. title match on March 25, 1979, in Toronto that went to a double count out in 39:10), a legends show in New Japan in 1990 where he put over Masa Saito (on the same night as Thesz's final match), a 1992 legends match at the Yokohama Arena against Robinson, with Thesz as referee, which was Robinson's final match, and his final match, on May 23, 1993, at the Omni in Atlanta, a legends match on the WCW Slamboree PPV show, where he went to a 15:00 draw with Dory Funk Jr.

If you found this article interesting consider becoming a Patreon supporter. That is how When It Was Cool keeps our website and podcasts online, plus you get lots of bonus content including extra and extended podcasts, articles, digital comics, ebooks, and much more. Check out our Patreon Page to see what's up!

If you don't want to use Patreon but still want to support When It Was Cool then how about a one time $5 PayPal donation? Thank you!